Magic Mountain’s creators had made a vision that appealed to many people in the region, and many snapped up stock offerings to help make it a reality. What the creators had not expected was opposition from their new neighbors.

Advent of Magic Mountain Announced

From the Colorado Transcript, May 30, 1957

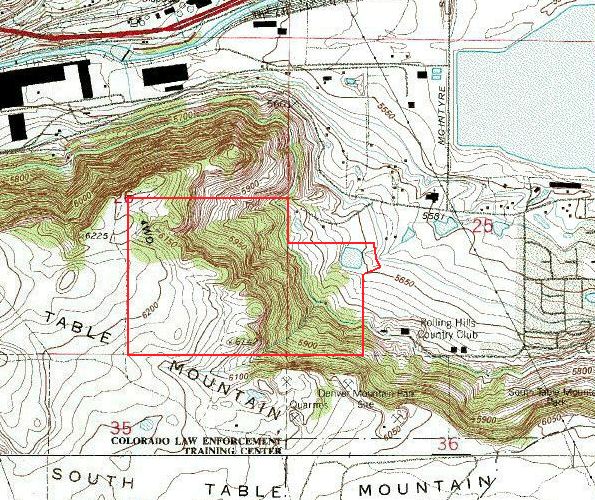

Magic Mountain Inc. had purchased 223 acres of the northeast alcove of South Table Mountain, with the option to bring the total up to 386 acres. Their location was breathtaking: a beautiful alcove on the northeast side of the mountain, framed by wild and scenic mountain slopes topped by towering lava cliffs. On the northern edge of the land under option was what the Transcript called “an outstanding pinnacle”, a majestic second Castle Rock that made a perfect location for the Queen’s Castle. Magic Mountain secured building permits from the County government on the express condition that the park remain a fairyland and not a more questionable form of amusement. The first foundation was poured at the beginning of June, 1957.

Map of first land area purchased to be Magic Mountain (outlined in red)

Exact boundaries of areas under purchase option are not presently known

Map courtesy United States Geological Survey

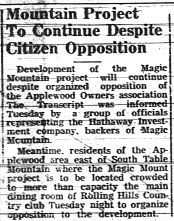

Quickly a whirlwind of controversy engulfed Magic Mountain. Residents of the Applewood subdivisions recently built to the east stridently opposed the plan. They believed that Magic Mountain would be popular all right, so popular that West 32nd Avenue, which gave access to it, would become a super highway, bringing much unwanted traffic, noise and people. Fears were raised that Magic Mountain would be another amusement park like the large ones already in the Denver area. Applewood home builders objected that since Magic Mountain had been proposed loan companies were noticeably avoiding making investments in Applewood homes. The Applewood Property Owners Association unanimously passed this resolution: “Resolved, that the Applewood Property Owners association authorize the president and the Board of Directors to take whatever actions they, on the advice of counsel, deem necessary and appropriate to oppose the development of facilities as proposed by the prospectus of Magic Mountain, Inc.”

The Magic Mountain Controversy

From the Colorado Transcript, June 6, 1957

Applewood’s reaction took Magic Mountain off guard. Cobb, himself a resident of West 38th Avenue, defended his proposal, stating “This will not be another Lakeside or Elitch’s. We want this to be educational with no excessive noise and no liquor.” Given Magic Mountain’s proposed concept, Cobb was correct in pointing out that rumors that Magic Mountain would be like the other amusement parks were unfounded. Magic Mountain officials also stated that there were three planned entrances to Magic Mountain, which in their view would alleviate the traffic impact on West 32nd Avenue. Where those other planned entrances were remains unknown; however, it is clear that 32nd would have provided the most direct access to the theme park in these pre-highway years. Officials of Magic Mountain also defended their project by taking the position it would increase land values and help the area’s small businesses because it would attract thousands of visitors to the vicinity. Magic Mountain’s impact of numbers, however, was precisely what Applewood feared, and this strengthened their resolve to fight Magic Mountain.

Suddenly, within a month or so, South Table Magic Mountain had vanished into the wind. Cobb and his associates found another, larger, 600-acre home, at Apex Gulch at the junction of the established Highways 40 and 93, at the base of the mountains. Magic Mountain’s early promotional materials had outlined two possible sites, South Table and this new location, expressing a preference for Apex Gulch. Magic Mountain’s signs were transplanted over there, and its creators examined and refined their dream. In the fall of 1957, Magic Mountain would begin to rise for real.

It seems likely that despite their initial defiance Cobb and Magic Mountain heard Applewood’s outcry, and walked away from South Table Mountain. It is not known whether any lawsuits were filed compelling Magic Mountain to leave, but media account of the time makes this appear unlikely. Cobb stated that rumors he would continue to pursue South Table were unfounded, and he wanted to build at Apex Gulch. This implies he had it within his power to continue at South Table Mountain, and given the fact Magic Mountain owned the land and Cobb had the building permits in hand, it appears he could have done so easily.

What became of the first home of Magic Mountain? Cobb early on stated the idea of building homes there, but he never did. The land instead found its way to the hands of the Coors family. Around the late 1960s what would have been Magic Mountain’s entrance, and the lake that was built, were given to Rolling Hills Country Club as part of an exchange for Rolling Hills’ original home since 1955 across West 32nd Avenue. Today the lake is part of the western edge of the Rolling Hills golf course. The rest of Magic Mountain’s land has remained wild, and will continue to be so. At the end of the 20th Century a conservation easement on this land was given to Jefferson County Open Space, including the rock of the Queen’s Castle.

South Table Magic Mountain was a grand dream that proved too overwhelming for its locale. It ignited the second of five known battles spanning a century to keep development off South Table Mountain, in the 1950s a public sentiment far ahead of its time and decades before major thought would be given to acquiring the mountain as permanent open space. It was a close call for South Table, the closest anyone has ever come to doing a large-scale development of that landmark. However, it may be a true testament to Cobb and to Magic Mountain that they chose to walk away rather than defy their neighbors when they were at their mercy, and instead choose to build at a place all could agree with. Ironically, in the end, the intervention of Magic Mountain at both its locations ultimately led to the preservation of hundreds of acres of the park’s cherished scenery, at both South Table Mountain and Apex Gulch. The failures of one dream enabled others in the future to come true.

Return to The Magic Dream Begins